How the British security services gained access to YOUR emails.

The news over the last few years has been awash with revelations about security services not only being able to ‘listen in’ on people’s communications, but that they are actively doing so, and even archiving that material. If it’s communicated electronically, there is every chance that it’s sitting in a database somewhere. For future reference. For the good of the country, and all that.

There are a number of different means used by the security services in order to achieve this, and one such is by building (or arranging to have built) deliberate flaws in systems, designed specifically so that the spooks are able to exploit it and gain access to the system, and thus to any data stored on it, or communicated through it.

As long-time users of RISC OS, you might raise a smile if you read or hear in the news about the latest information on this subject being leaked to the press by whistle-blowers like Edward Snowden, when those leaks reveal that the big American corporations like Apple, Microsoft, Google, and so on, are affected by such exploits, or are complicit in their presence in their systems.

But the latest revelation is… that you shouldn’t be smiling at all.

RISC OS, it seems, is not immune to any of this.

In truth, security has never been one of the operating system’s strong points – anyone who understands basic principles should realise this, and we RISC OS users are really only benefiting from security by obscurity, which basically means we are just riding our luck.

However, it seems that luck hasn’t just run out – it was never there to start with, and we only ever believed it was.

I have seen a number of documents, a mixture of internal memos, technical documents, copies of inter-department communications, and so on, leaked to me by an insider at GCHQ, which reveal that RISC OS was compromised by them at the request of both the Security Service, and the Secret Intelligence Service, in the name of national security back in the 1990s. Furthermore, this compromise didn’t just take the form of an exploit that could be made use of at some point in the future.

No.

Code was implemented in a number of places to actively copy data directly to a GCHQ server for sorting and storing – and it appears that code may very well still be in place and working, on both forks of the operating system.

Before looking at the code itself, where it is in the operating system and what it does, it’s worth trying to understand why the operating system we now think of as a niche one, with a very small user-base, was ever targeted in this way.

The key point is that we now see the operating system as a niche one, with a very small user-base – but it wasn’t always so. Judging by some of the leaked documents, which are from the early 1990s, it appears that Acorn – and in particular its ARM processors (which had by then been spun out into a different company, ARM Ltd) and the operating system that ran on them, RISC OS – were seen by the security services, as having great potential, and that they could have led to a British designed computer system becoming a widely used platform around the world. For the general public, the internet was still something new, and hadn’t yet taken off in quite the way it would later in the decade, but all the signs pointed to it doing just that, so with the prospect of a British computer system that looked as though it could ultimately be found in such widespread, worldwide use, and able to make use of the internet, it was quite clear what that could mean for the services – SIS in particular – if the right steps were taken at the time.

So the decision was made.

It appears that a small team was tasked with infiltrating Acorn, by gaining employment as part of the development team – knowing that not all would get in, perhaps 1/4 of them – with a view to incorporating the necessary code in the operating system, and making it look as innocent as possible, while also being hooked in as widely and deeply as possible, so as to ensure it would be both hard to remove, and sure to be called.

There are three key parts to the code, each of which is designed to carry out one part of the overall process, but each of which is in a different module buried deep in different parts of the operating system, so as to make it harder to see just what is really going on.

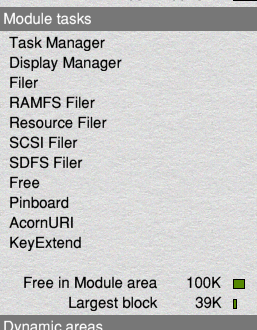

The first of these modules is called ‘sbby‘ – a name that seems meaningless, but may very well mean something that isn’t made clear in the leaked documents I’ve seen – and is supposed to be hidden, so that under normal circumstances a user wouldn’t know it is there. It doesn’t show up at all in the list of modules found by typing *modules or *help modules at the command line, for example, though a bug in the code does cause it to show up under some circumstances as a blank line in the list of module tasks shown in the Task Manager window, as can be seen here in the screen grab of my own system.

It is seemingly possible to quit the module from here, which causes it to disappear from the list of module tasks in that window – but the reality is that it simply restarts itself, without showing up as a module task, although the same circumstances that caused it to appear as a blank entry in that list in the first place can reoccur at a later point, causing it to appear in the same way again.

If you are reading this on a RISC OS computer system, or if you have a RISC OS system on your desk and switched on, it’s worth looking now at the Task Manager window to see if that blank entry is there in the list of module tasks. Just click with Select on the ‘Switcher’ icon at the far right of your icon bar, and scroll the window that opens until you see the list of module tasks. Is that empty entry there? If so, the sbby module is definitely running on your system, and the bug – the exact nature of which I haven’t been able to determine – has caused it to appear. If it isn’t there, don’t for one moment assume that means it isn’t present on your system – that it isn’t in the list just means the bug hasn’t been triggered.

How the module seems to work is that it monitors the system, keeping an eye out for when the user is about to upload data to servers on the internet – such as when sending an email, for example.

The second hidden module, with the equally inexplicable name ‘ncevy‘ – which doesn’t appear to suffer the same bug as the first; it doesn’t ever show up in the list of module tasks – is then called with SWI &1335171 (or ncevy_sbby) with r0 containing t13. This module intercepts the data being uploaded by the user, and prefixes it with a special sequence of characters, designed to be recognised by the third batch of hidden code, which is craftily hidden in the DNS Resolver module.

This final step is therefore implemented in the way RISC OS talks to the internet – and this is particularly cunning. The Resolver module is designed to take the name of a server, such as www.riscository.com, and determine the numeric address of that server on the internet – but when it detects the special sequence (the values &20417072, &696c2066, &6f6f6c21 in the first three words of the packet) – it knows that it needs to do something else. Rather than return the real numeric address of the required server, it returns the address of the GCHQ server in its place, sending a message to the GCHQ server with the real destination address for the data that is about to be sent.

The software being used on the computer, therefore, innocently sends the data to the GCHQ server, which adds a copy of it to its own archives, and then passes it on to the real server, the one the user actually intended the data for. Thus, as far as the user and the real server is concerned, everything that was sent has reached its destination, and nothing appears untoward.

In recent years, the web browser of choice for most RISC OS users is probably NetSurf. One of the interesting features of NetSurf is that it doesn’t use the Resolver module found on RISC OS computers – it uses its own. Given that the core developers know a thing or two about security, it’s not a huge leap of the imagination to wonder whether they chose to go down that route because one or more of them had become aware of this long-implemented backdoor, and saw this as a way to circumvent it.

Either way, that the platform is (now) only a minority one, with comparatively few users, means the amount of data collected by this scheme isn’t much, and can’t be as valuable to the services as they once thought it might be, and may not even justify the cost involved in setting it up and maintaining it, a cost now borne solely by GCHQ – and at the very least, they have to maintain the server to which uploaded data is diverted from RISC OS machines, in order to allow those machines to continue to work properly on the internet.

And if the worth of this scheme to GCHQ is so low, then that is something of a victory for the average person – but if that average person is a RISC OS user, who’s many emails, etc, are now stored in an archive on a GCHQ server?

Then that victory is a hollow one. A hollow one indeed.